|

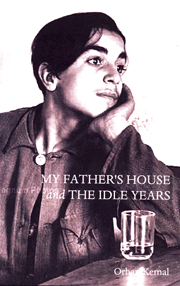

On Orhan Kemal's The Idle Years

Novels are a source of comfort and psychological sustenance to their

readers, but they can be so to their writers too. This is especially

true for writers working in an autobiographical mode. The novel,

here, is like a beam turned in upon oneself, lighting up old shadows

and nooks -- or it might be thought of as a mirror in which one's

old faces successively appear. The forward march of the narrative in

this case also a backward journey into time, and the slow time and

fruitful agitation of writing throw up memories long submerged.

These are the speculations occasioned by The Idle Years, a novel

first published in two parts in 1949 and 1950 by the great Turkish

writer Orhan Kemal (often referred to in the English-speaking world

as "the Turkish Dickens"), and now newly and strikingly translated

by Cengiz Luhal. Although it is sometimes a mistake to link a

writer's books too simply to his autobiography, it would seem that a

discussion of The Idle Years would at least begin with such a

reading.

The unnamed narrator of the book is the son of a charismatic

political agitator who is sent into exile with his family after

falling foul of the Turkish regime in the 1920s. Brought up in a

large house with all the comforts of life, the protagonist is

suddenly pitchforked into a life in which the family is always on

the move, money is scarce, and the father's temper thunderous. He is

forced to work at menial jobs, and begins to keep the company of a

set whom he had previously seen only from afar, and with no

consideration of their miseries: workers, vagabonds, and prostitutes.

He is constantly hungry, and when granted a good meal through luck,

comradeship or charity not only eats ravenously but also remembers

every dish and every helping for days. He is often consumed by

despair and by shame, but most of all loathes the heavy hand and

bellowing voice of his father.

This story broadly follows the contours of Kemal's own youth, and it

might be seen as part of that current in literature in which writers

mull over the weight placed on their lives, in both good and bad

ways, by their fathers: the early novels and later autobiographical

meditations of VS Naipaul, for instance, or Franz Kafka's anguished

Letter To My Father, or even the essays of Kemal's famous countryman

Orhan Pamuk (whose Nobel Prize acceptance speech is called "My

Father's Suitcase", and who has written a short, admiring foreword

for this book).

Indeed, the first part of The Idle Years is called My Father's House,

and its closing movement is one in which the protagonist resolves to

leave that house, and returns from Beirut to his homeland to strike

out on his own. In one of the novel's best passages, the narrator

returns to his hometown, Adana, hot with stories of his itinerant

life to tell his childhood friends, only to find that nothing is as

it used to be. The place the heart thinks of as home is a pillar to

one's self but fragile on its own terms.

Kemal's novel beautifully evokes the world-changing ardour and angst

of youth, the consolations of friendship, the aches and burns of

love, and the redemption of constant misery and hardship by small

acts of kindness or brief interludes of escape. He is considered a

great writer of dialogue, and in Luhal's translation the reader can

see why. Many of his characters are real talkers, but they talk in a

stop-start and naturalistic fashion, leaping from one subject to

another, or revealing some particularity of their character through

a repeated emphasis. They don't always know what they are saying,

though characters in other kinds of novels seem to.

The Idle Years ends with a scene in which the protagonist, still

impoverished, marries his beloved wearing a borrowed suit, shoes,

and tie. The newlyweds are excited by the beautiful gifts that they

have been given, and begin to construct a castle of dreams upon them,

only to find out that the groom's grandmother borrowed them all from

family and friends to give the wedding a glitter, and that the goods

must now all be returned. This episode is symbolic of the whole

story, in which hope and yearning are always trying to break free of

the chains of reality, and disappointment is quickly forgotten. The

last line of Kemal's novel - "So we carried on with our lives,

appreciating all that we had" - seems both an observation of a fact

and a piece of friendly advice to the reader.

And some other essays on Turkish literature: "Nazim Hikmet in prison"

(Hikmet and Kemal were contemporaries, and spent time in prison

together, and indeed one register of The Idle Years is distinctly

Hikmetian), "Orhan Veli Kanik all of a sudden", and "On Orhan

Pamuk's My Name Is Red".

Chandrahas, 11:28 AM

|