|

From the earliest days of the Republic, literary writers who

challenged Turkeys official ideology could expect to spend

time in prison. Despite the privations that they suffered

behind bars, they were able to form societies of support

that helped them grow as writers while also helping them to

survive materially. Though todays literary writers are

unlikely to spend time behind bars, they do not always feel

better off.

In 1938, while doing his military service, a young Turkish

poet named Raşit was charged with inciting mutiny and

spreading propaganda on behalf of a foreign state. The

evidence against him was slim but, in a court that regarded

Communism as the single most important threat to national

security, not unusually so. Among his belongings, the

authorities had discovered an assortment of newspaper

cuttings about Marxism, a book by Maxim Gorky, and a handful

of poems dedicated to Nâzım Hikmet, who was not just

Turkeys first and foremost modern poet but also its most

famous Communist.

Raşit was dispatched to a prison in the city

of Bursa to serve out a five-year sentence. The winter of

193940 found him assigned to the prison register office.

One morning, the registrar walked in to say, Youre in

luck. Your masters coming. When Raşit protested, saying,

I dont have a master, or anyone else who fits that

description, the registrar thrust a document into his hand:

Look at this, then. Nâzım Hikmet. Dont you reckon hes

your master? (Orhan Kemal in Jail with Nâzım Hikmet).

Though Bursa Prison was a broad church, mixing its political

prisoners with thieves, drug dealers, murderers, and

bandits, every inmate knew of the great Nâzım Hikmet. Those

who had come to know him personally in other prisons painted

a picture of a man so much larger than life that he could

stun a crying baby to silence just by picking him up. So

Raşit was not prepared for the bright-eyed, open-faced man

who walked through the door, clicking his heels together

like a soldier as he introduced himself. As he scanned the

room, his face lit up at the sight of each familiar face.

And youre here as well, Vasfı? What happened to your

appeal? . . . Then what next, Remzi? So you got thirty years

then? What on earth for?

He was assigned to one of the isolation cells usually

reserved for men caught gambling, thieving, or knifing a

fellow inmate (though in this case it would have been an

acknowledgment by the prison authorities that he was a

distinguished man of letters who should not be obliged to

live communally with common criminals). Raşit was on hand to

help Nâzım settle into his new quarters. After Raşit had

cooked them both a meal of eggs and Turkish sausage on his

charcoal brazierand refused to let his guest pay for his

shareNâzım asked if he would mind being his roommate. I

cant stand being alone! You cant even imagine. . . . I

cant write a single word. I just go mad.

It wasnt long before Nâzım, having already decided to tutor

Raşit in French and current affairs, asked to hear a few of

his poems. Raşit began with the one of which he was most

proud. He had not reached the end of the first stanza when

Nâzım said, Thats enough, brother, thats enough . . .

lets go on to another one, please He did as he was told,

but he had hardly begun the poem when Nâzım cried, Awful!

Feeling very small, Raşit embarked on a third poem, only to

be told, Ghastly!

All right, brother, Nâzım said then, but why all this

verbiage andexcuse the expression mumbo jumbo? Why do you

write things you dont sincerely feel? Look, youre a

sensible person. Dont you realize youre maligning yourself

when you write about what you feel in a way that youd never

feel, that youre making a mockery of it like that? Having

launched into a long lecture about active realism that

Raşit, in his humiliation, could barely understand, Nâzım

again stunned his new friend, this time by asking if he

would like to hear him read.

I pulled myself together, Raşit later recalled. We were

facing each other, eye to eye. He added: But youre not

going to be just polite about them. Youll also criticise

memercilessly!

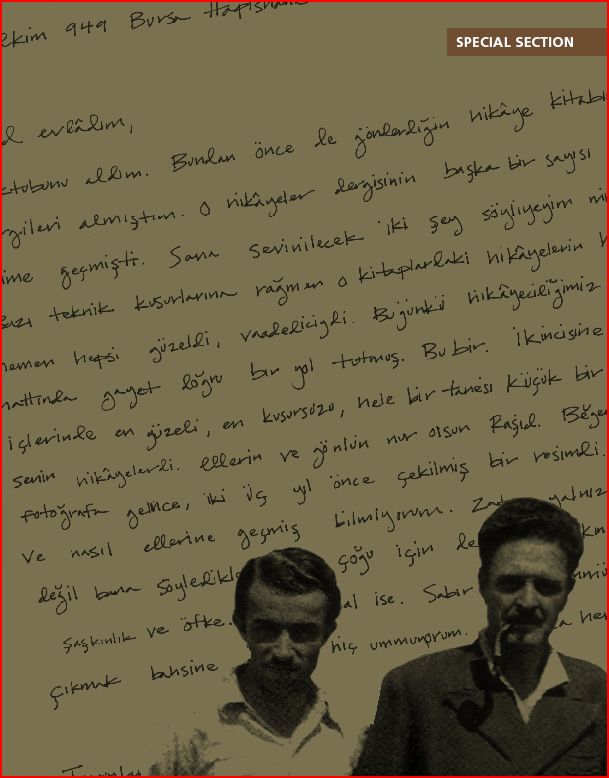

Thus began one of the most touching friendships in Turkish

letters, which Raşit later recounted in a short memoir

entitled Nâzım Hikmetle üç buçukyil (Three and a half

years in prison with Nâzım Hikmet). Though he wrote it in

1947, the book was not published until 1965. By then Raşit

had become the famous (though forever struggling) novelist

Orhan Kemal (the pen name by which he is known in Turkey),

much loved for his stark tales about the poor and

downtrodden. Nâzım Hikmet (190263) had been dead for two

years, having spent more than thirteen years of his life in

prison and his final twelve years in exile in the Soviet

Union.

Though it would continue to be dangerous (and, at times,

illegal) to own a volume of Nâzım Hikmets poetry, death

would not silence him, and neither would it lessen the

stature of Orhan Kemal (191470). To this day, they are

loved even by those compatriots who do not share their

politics admired not just for their words, but for the sort

of men they were, and for the code by which they lived.

Nowhere is their generosity of spirit more beautifully

described than in Orhan Kemals jewel of a memoir, now

beautifully translated into English by Bengisu Rona.

The volume includes a long essay that sets the memoir in

historical context, outlining the two writers careers and

explaining (though never condoning) the mind-set that led to

the persecution and prosecution of writers at odds with

state ideology. During the early years of the Turkish

Republic, as he struggled to pull together the shattered

fragments of the Ottoman Empire to create a unified

nation-state, Mustafa Kemal Atatürks success depended on

his manufacturing (and, if necesssary, enforcing) consent

among intellectuals, religious conservatives, and the

diverse Muslim ethnic groups that now made up most of

Anatolia. If ever he met with dissent that threatened to

weaken the Republican project, he was quick not just to

suppress it but to be seen as suppressing it decisively.

Always suspicious of Turkeys Communists, he was

nevertheless willing to enter into alliances with the Soviet

Union if he judged them advantageous, and when these

alliances were in place, the curbs on left-wing expression

would lessen. But by 1938 Atatürk was on his deathbed, and

those who succeeded him were less flexible.

For most of the next half-centuryuntil the emergence of the

Kurdish separatist movement and the rise of political Islam

in the 1980sit was leftist intellectuals whom the Turkish

state viewed as the most dangerous threat to national

security, and it was prepared to use the harshest measures

to stamp out any party or movement that might be taking its

orders from Moscow. Turkeys first penal code, taken from

Mussolinis Italy, contained several articles prohibiting

organizations and propaganda seeking to destroy or weaken

nationalist feeling. These were deployed aggressively

against the left-wing intelligentsia in general and

left-leaning literary writers in particular, though almost

always it was literary writers political statements that

led to their prosecution. Many thousands of leftists and

alleged leftists were imprisoned in the aftermath of the

1971 coup; many more were imprisoned after the coup on

September 12, 1980. There was even a time, following the

1980 coup, when the penalties for writing an essay urging

the Turkish people to take up arms against the state were

more severe than those applied to those who actually took up

arms against the state. Leftleaning journalists would often

find themselves prosecuted for a host of articles

simultaneously; for these they were sometimes given

consecutive sentences that, added together, would have taken

several lifetimes to serve out.

Though there were periodic amnesties, leftist writers often

found life outside prison more difficult than life inside.

After their release, they were often sent into exile in

remote parts of the country, particularly in the early years

of the Republic, though the practice was still in place in

the 1970s. When they were at last able to return home, many

would find themselves barred from secure employment. Often

the only recourse was to work as freelancers in publishing,

but even if they were as famous and prolific as Orhan Kemal

(who ended up publishing twenty-eight novels, eighteen

short-story collections, two plays, and two memoirs, as well

as writing many film scripts) they were unable to earn a

living wage. As is so often the case in the face of

sustained persecution and harrassment, Turkeys left-wing

writers survived by helping one another.

This may explain whyeven today, when, strictly speaking, it

is no longer accuratethe joke in Turkish literary circles

is that you are not a true writer until you have spent

some time in prison. What is at stake here is not an

aesthetic but an ethos, and in Orhan Kemals portrayal of

Nâzım Hikmet we see its roots. Though his own origins were

rather grand, Hikmet saw himself as a peoples writer.

Though politically an internationalist who believed in the

struggle as defined by Marx, he was a fervent patriot and

endlessly enthusiastic about the potential of our people.

One of his most famous poems is a wish (still unfulfilled)

that he be buried under a tree in Anatolia. In another

much-loved poem, he offers a set of instructions to those

who find themselves in prison:

There may not be happiness but it is your binding duty to

resist the enemy, and live one extra day. Inside, one part

of you may live completely alone like a stone at the bottom

of a well. But the other part of you must so involve

yourself in the whirl of the world, that inside you shudder

when outside a leaf trembles on the ground forty days away.

(Beyond the Walls)

It is the same struggle to sustain hope against the odds

that we witness in Orhan Kemals memoir, and in the letters

that Hikmet writes to him after his release (also translated

by Rona and included in the volume). No matter how bad

things are, Hikmet refuses to bow to his oppressors. He is

the one who goes to the prison authorities to speak on

behalf of prisoners too frightened or too shy to ask for

dispensations. He tutors not just the poets in the prison

but the would-be painters. Lacking the means to support his

wife and child or to pay for his upkeep in prison, he sets

up a weaving business. He is painstaking about paying all

those involved in the business fairly, and in his letters to

friends on the outside, he devotes much space to chiding and

cajoling them into doing a better job of selling their

wares. He is an ardent listener, passionately interested in

the stories told to him by his fellow prisoners, many of

whom will go on to be immortalized in his poems. But

throughout all this, he retains the wayward exuberance of a

child. When his wife comes to visit, he flaps his arms in

excitement as he speaks, while she, the dignified and

long-suffering wife of a great poet, sits silent and

composed. When his mother comes to visit, she listens

respectfully to his poems, but because she knows herself to

be the better painter, she is scathing about his art, and he

receives her criticism with a bowed head. When Raşit gives

him a rabbit, he is so fiercely affectionate that the rabbit

almost dies of fright. And when Raşit becomes Orhan Kemal

and sends him his latest book, his mentor begins by offering

yet another punctilious writing lesson, outlining the

novels strengths, listing its shortcomings, and expressing

horror at the dreadful photograph chosen to appear as the

authors picture in the book. There follows yet another

lecture about the eroding effects of despair on literature:

Beware, my son, protect yourself from this, be even more

bitter and sad, but let your joy and hope shine through.

Thats it. I repeat once more, I congratulate you and

Turkish literature. Young and old, I clutch you to my

bosom.

In this age of irony, it is hard to imagine a writer

offering up such undoctored sentiments, even if that writer

comes out of the literary tradition that Nâzım Hikmet and

Orhan Kemal helped forge. The spirit of resistance remains

strong among the many fine journalists whose principles

oblige them to challenge state ideology. But among todays

literary writers, the center has not held. Most acknowledge

their debt to the the great mid-century fiction writers of

the leftist tradition Sabahattin Ali, Aziz Nesin, Kemal

Tahir, and Yaşar Kemal, to name just a fewand some (like

Latife Tekin) are happy to see themselves as continuing that

tradition. But todays novelists are less likely to see

themselves as writing for the people, let alone the

struggle, and more likely to resist the idea that their work

only has worth to the extent that it serves the national

project (however they define it). They speak instead of the

primacy of the imagination, the need for a distinct and

authentic voice, and the importance of writing about the

world as they themselves see it, unimpeded by ideology.

Sadly, there are many in the state apparatus who are as

suspicious of todays most successful literary novelists as

their predecessors were of Nâzım Hikmet. They do not like

writers breaking with the official ideology or airing their

independent opinions abroad. In Turkeys penal code of 2004,

ostensibly brought into line with European social democratic

norms, there are up to twenty articles that curb free

speech, the most famous of which is Article 301, which made

it a crime to insult Turkishness, along with the Turkish

Republic, parliament, the government, and judicial

organsand the army and police for good measure. Since its

introduction, only a few of the hundreds of prosecutions

have led to prison sentences, and in no case has a

well-known writer of fiction been jailed. However, the

much-publicized prosecutions of Orhan Pamuk and Elif Shafak

did succeed in giving prosecutors a platform on the evening

news, while portraying the defendants as traitors. After

persistent criticism of this clause, some minor amendments

were introduced in 2008, replacing the word Turkishness by

the Turkish nation and reducing the maximum penalty from

three to two years imprisonment. None of the critics of

Article 301 has been impressed by the changes.

Kemal Kerinçsiz, the ultranationalist lawyer who launched

both the Pamuk and Shafak prosecutions, also launched

several against the Turkish Armenian journalist Hrant Dink;

following a sustained hate campaign in the ultranationalist

press, Dink was gunned down in front of his office in

January 2007. His assassin is behind bars, though his fate

is still unclear: his trial is expected to go on for years.

Also behind bars is Kerinçsiz himself. In early 2008 he

(along with many others) was charged with belonging to a

state-sponsored ultranationalist terrorist organization

charged with aiming to soften up the country for a coup. It

is alleged that this organization had a hit list, and that

Orhan Pamuk was to have to have been its next target. This

trial, too, is expected to go on for a decade.

In the meantime, Pamuk lives under police protection when in

Turkey. Though he can come and go as he likes, and though he

is free to speak his mind, he is wise enough to exercise

extreme caution, for he knows (as do all other leading

writers who have been targeted by ultranationalists in

recent years) that a single unconsidered sentence in an

interview with a journalist anywhere in the world could lead

to a renewed hate campaign.

For a political journalist or a human rights activist, such

risks, however undeserved, might still be said to be part

of the job. For literary writers wishing to free themselves

of all political ideologiesnationalist and

internationalist; left, right, and centerthe question is

more complex. Where to find the space to work, safe from the

glare of publicity? How to explore ideas openly if ones

every word is subject to hostile scrutiny? How to reclaim

the capricious sense of play without which the imagination

cannot function? During the three-and-a-half years Nâzım

Hikmet shared a cell with Orhan Kemal, the two men were

able, despite the many hardships, to create a space, and a

tradition, that allowed them to hold Turkish literature to

their hearts. To read of their friendship now is to

understand how much harder it is for Turkeys literary

writers, for all their fame and all their freedom, to find

such spaces today.

University of Warwick |