My

Master, My Friend

|

|

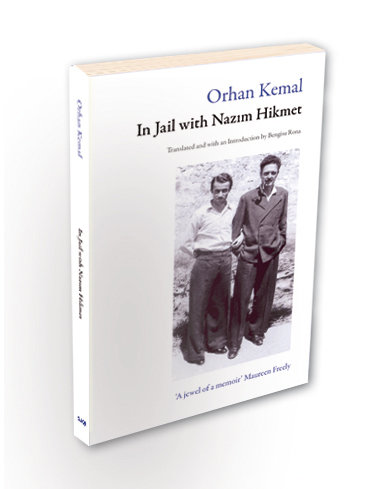

Turkish writer Orhan Kemal recounts three years in prison

with acclaimed poet, Nazim Hikmet

Published: Thursday 12 August 2010 Updated: Thursday 12

August 2010

In a dank bug-infested prison some 50 miles from Istanbul,

aspiring writer Orhan Kemal meets one of Turkey’s most

famous poets, Nazim Hikmet. For Orhan, this is the meeting

of his lifetime. For Nazim, this is an opportunity to shape

who was to become one of Turkey’s most “foremost writers.”

Orhan Kemal’s memoir, "In Jail with Nazim Hikmet," gives us

insight into the lives of ordinary Turkish people during the

long and painful period of nation building aggressively

imposed by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, leader of the new Turkish

republic. At the same time, we are drawn into prison life

and the close friendships that make it bearable.

In Jail with Nazim Hikmet

Orhan Kemal

Saqi Books 2010

£10.99

“Your master’s coming.”

“No,” Orhan said, “I don’t have a master—or anyone of the

kind.”

“Look at this, then. Nazim Hikmet. Isn’t he your master?”

Indeed, Nazim Hikmet, counted among the most acclaimed

Turkish poets of his day, would soon become Orhan’s master

and his friend, so much so that Nazim wrote in a letter

addressed to Orhan dated 1947, “Sometimes I feel the sadness

of separation from you very acutely; sometimes I feel the

joy of thinking of you all being very happy. Your pictures

and your photographs are all there at my bedside.”

Orhan looked at the name printed on the register, confirming

the arrival of Nazim to Bursa prison some weeks later.

Bursting with the joy of a child, Orhan couldn’t help but

spread the word of Nazim’s arrival to his fellow inmates.

Everyone, it seemed, had a story to tell; he was the kind of

man whose presence inspired action.

For most of us, the idea that we would have the chance to

meet our most revered and respected role model is impossible

to imagine. Immediately humbled in the presence of such a

person, one would feel it difficult to know just what to do.

Orhan was no different. When pressed by a friend about his

work on the first day of their meeting, the young writer

told Nazim that he had penned nothing more than “scribbles”

of poetry, when in fact he had written prolifically (but not

necessarily competently) prior to his conviction, and also

during his sentence, the first two years of which he had

already served.

It was not long before Nazim took it upon himself to

instruct Orhan with the goal of enhancing his education and

improving his writing, eventually convincing Orhan to give

up poetry in favor of prose. With one of the most prominent

poets in the country as his mentor, Orhan progressed

quickly, becoming, as Nazim had predicted, “… one of the

foremost writers of my country.” By the year of his death in

1970, he had published 28 novels, 18 short story

collections, two plays and two volumes of memoirs, as well

as a book of essays on the technique of writing film

scripts.

Orhan Kemal’s prison memoir, In Jail with Nazim Hikmet,

provides us with a valuable insight into the development of

Orhan as a writer, as well as the political and social

context in which the two men lived. Translated and

introduced by Bengisu Rona, Reader in Turkish at the School

of Oriental and African Studies, this book is a quick and

rewarding read. One need not be familiar with Turkish

literature to appreciate Orhan’s story. In addition to the

text itself—written chronologically—Rona provides us with a

lengthy introduction to the lives and works of Orhan Kemal

and Nazim Hikmet, who met as political prisoners of the

increasingly harsh Atatürkian state. At the end of the book

we have Orhan’s “Prison Notes,” from which Orhan constructs

his memoir, and “Letters from Nazim Hikmet to Orhan Kemal,”

through which we can witness further the deep bond between

the two men.

It is through this close and inspiring friendship, which

develops during their three years together in Bursa prison,

that we are introduced to the lives and characters that, in

a very real yet gradual way, played a role in the building

of Atatürk’s modern Turkish republic. At the time of their

meeting, Nazim, a well-known communist, was serving a

27-year sentence for allegedly instigating mutiny in the

navy. It was in prison that he gathered much of his material

from which to write his poetry. Like Nazim, Orhan was also

convicted of inciting mutiny, in addition to allegedly

producing propaganda on behalf of a foreign state (Russia),

for which he served five years.

The severity of their sentences and others like them can be

attributed to the state's fear of a communist threat coming

from Russia, which had begun to develop during the inter-

and post-war periods. Lacking in political and military

support after the fall of the Ottoman Empire, the

nationalist leadership in Ankara looked to Russia, allying

itself with the Bolsheviks. However, as is characteristic of

expedient relationships, when Soviet assistance became less

dire, the voices supporting a communist takeover within the

country became more problematic. Political assassinations,

and massacres in some cases, became the norm, and it was

this policy that saw the imprisonment of Nazim Hikmet and

Orhan Kemal.

Among the many accomplishments of this book is its ability

to sell itself: Read it and you will want to read more.

Nazim and Orhan were not just outstanding writers, they were

outstanding people, who played an important part in the

birthing of their nation. The insight into the lives of

these two writers through Orhan’s own words is priceless.

Full of love and friendship, courage and perseverance, the

principles by which these men lived are noteworthy in both a

personal and historical context.

As the first writer to introduce the emergence of

industrialization into Turkish literature, Orhan’s

characters endured starvation, death and misery, however he

always remained loyal to Nazim’s assertion that “… a writer

who offers no hope has no right to be a writer.” And for

that, Orhan always offers us hope. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|