|

Nazým Hikmet

22 July 2012 / ALISON KENNY , ANTALYA

I visit Antalya's splendid, centrally located Karaalioðlu

Park twice daily in the company of my sometimes (in the

current summer heat) reluctant dog. Around a year ago I was

surprised to see that the giant hand statue adorning the

harbor-end of the cliff-top promenade -- formerly a popular

spot for tourists to clamber inside and pose amusingly for a

photo -- had disappeared.

In its place was a weird looking angular monument,

consisting mostly of great slabs of stone covered in

writing. On close inspection the words turned out to be

extracts from the works of a man I later discovered was

Turkey's most famous poet, Nazim Hikmet, a man who had spent

most of his life either incarcerated in one of Turkey's

jails or living in exile in Russia.

Understanding Turkey's culture is a complex business, but

taking the time to sniff out Turkish literature that has

been translated into English is well worth the effort.

Ýstanbul obviously has a generous selection of bookshops

well stocked with English versions of several Turkish

authors. Antalya, where I live, has a rather more limited

choice, but for a long time, inspired by my daily glimpses

of these poems, I have been interested in finding out more

about Nazim Hikmet.

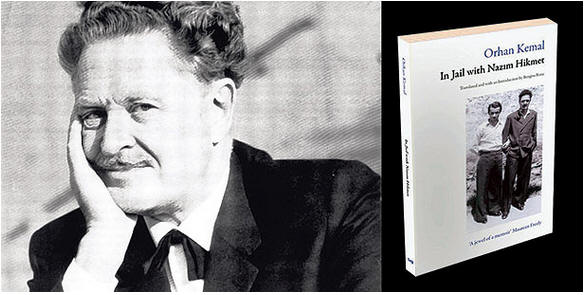

So I was delighted to stumble on a book by another famous

Turkish author, Orhan Kemal, in an Antalya shopping mall. In

the slim volume Kemal details the time he spent in prison

with fellow writer, Nazim Hikmet. “Brilliant,” I thought, “a

fantastic introduction to two Turkish literary giants in one

go.” Both men had been imprisoned for “inciting”

revolutionary thoughts amongst their fellow soldiers while

serving time in the army through their writing, teaching and

meetings. Nazim had been sentenced to 28 years and Orhan to

just five. Nazim was transferred to Bursa prison on health

grounds, and the two men spent the next three-and-a-half

years, sharing a cell, their food, their ideas and, of

course, their writing.

Orhan Kemal

Orhan Kemal was born in Ceyhan on the Çukurova plain near

Adana in 1914. His mother, unusually for that time, was

educated and had worked briefly as a teacher. His father

became a writer and a lawyer but because of his largely

left-wing, independent political leanings the family moved

several times and eventually fled to Syria and Lebanon in

1935. Orhan's formal education suffered from this upheaval

and in his formative years, he worked in Ýstanbul and Adana

on a variety of jobs, providing him with a whole range of

excellent material for his future novels.

Three-and-a-half years with Nazim Hikmet

Orhan was already a fan of Nazim's work and familiar with

many of his poems -- “Orchestra,” “Mechanization” and “The

Caspian Seas” to name but a few -- and he quotes from these

liberally and excitedly on hearing the news of Nazim's

imminent arrival in the otherwise stultifyingly boring

atmosphere of the prison. We get a flavor of his style --

modern, colloquial and direct as in this snippet from

“Mechanization”:

“I want to be mechanized!

It comes from my brain, my flesh, my bones!

I'm driven mad by the desire to take over every dynamo I can

lay my hands on!”

Nazim's entrance into prison and introduction to fellow

inmates gives us a clue to his magnetic personality. He

greets former prison acquaintances from all walks of life

with an abundance of kindness and interest, exuding an air

of optimism in all directions. Within the first two hours of

his arrival, Orhan had shared his meal with the great poet,

and they mutually decided to share the room and the cost of

their living expenses. Orhan, on request, attempts to read

some of his own “scribblings” to which Nazim responds with

“awful” and “ghastly,” but sees beyond these and offers to

help Orhan with his education. The book proceeds to chart

the intense relationship between the two men and the

influences and experiences that helped shape the poems Nazim

wrote during this period.

Nazim Hikmet

Although born in 1902 in Salonica, he was brought up largely

in Ýstanbul. His father worked for the foreign office, his

mother was an artist. He attended the naval school for

several years but was discharged on health grounds. He

became politically active through his writing and

particularly interested in left wing/Marxist ideology. He

first went to the Soviet Union in 1921 and in his absence

was given his first prison sentence. He returned to the

country illegally in 1924 and was immediately arrested.

During his life he spent much time travelling, particularly

in Russia and Poland, before dying in 1963 in Moscow. He

began his writing during politically turbulent times --World

War II, the struggles with Greece and the Turkish War of

Independence and, later, the lead up to World War II.

Throughout this latter period, Turkey had an uneasy and

tenuous relationship with Russia, possibly explaining the

severe 28-year sentence that he received for encouraging

Marxist views in both the army and navy.

The poems

I was particularly interested to find out just why Nazim

Hikmet was, and remains today, such a well-known figure,

particularly as he was perceived as an enemy of the state

for most of his life. But this book, with its beautiful

translations of the poems written prior to his sojourn in

Bursa prison and those during his time in Bursa, go a long

way to explain his importance in Turkey's literary history.

His writing follows on from the more formal traditions of

the Ottoman style. He writes passionately about subjects

close to his heart -- both on the large scale and on the

personal level. Orhan Kemal's book not only brings to life

Nazim Hikmet's character through his relationships with the

other prisoners, the visits from his wife and his ongoing

interest and concern with Orhan's family, but also puts into

context some of the poet's great pieces of work.

His epic poem “Human Landscapes from my Country” was

composed largely during his stay in Bursa prison. This

includes sections on the War of Independence and Hitler's

invasion of the Soviet Union, and these are interspersed

with vignettes of characters from amongst his fellow

inmates. His opening lines describe Galip Usta:

“At Haydarapaþa Station

Spring 1941

It's three in the afternoon

On the steps, sun, exhaustion, stress.

A man is standing on the steps thinking about various

things.

He's thin, timid with a long pointed nose,

His cheeks covered with pock marks.

The man on the steps is Galip Usta,

who's famous for thinking strange thoughts.”

Orhan explains that for Nazim it was crucial to his work

that people understood his poetry. He used the opportunity

in prison to read aloud over and over again his work and to

refine them accordingly in order to make them more

accessible and for them to be understood and felt by

everyone. The effect of his poems on his audience was always

remarkable, with many being reduced to tears or encouraged

to recall incidents from their past.

Understanding something of the background to this literary

genius has helped me at least to recognize the importance of

Nazim Hikmet and to begin to appreciate the beauty of his

work. This book was so expertly crafted and such a pleasure

to read that I am inspired now to search out some more works

by both Nazim Hikmet and Orhan Kemal. This may necessitate

yet another trip to my pet hate -- a shopping mall -- but it

will be well worth the sacrifice.

Comments:

Valley , 24 July 2012 , 01:42

Soluting Nazim Hikmet and wishing as a nation we will stop

once and forever to persecute our writers/poets. And try to

go beyond ourseves to understand the messages they try to

convey.The footprints left behind, that he was here once is

everywhere around us. His name inspires new generation of

true tellers.And today comes almost natural, of speaking the

mind, perhaps because of people like Nazim Hikmet, Sebahatin

Ali, came before us and pioneer for all to be proud of our

identity.They came from all over the places of the past

Ottoman Empire, but the bottom line is = we all are Turks.

Mel Kenne , 23 July 2012 , 16:05

Dear Alison Kenny, Thank you for your article about Nazim

Hikmet and the book written by Orhan Kemal about the time he

spent in jail with Nazim Hikmet. It is indeed a fine book,

and I would like to remind you that such books as this are

only accessible to readers who do not speak Turkish because

of their translators. While you do mention translation in

your article, and even speak of the "beautiful translations

of the poems," not once in the article is a translator's

name mentioned. The translator of this book, who also wrote

the long and very informative introduction, is Bengisu Rona,

a professor of Oriental and African Studies at the

University of London, and a member of our Cunda Workshop for

Translators of Turkish Literature. Too often when we read a

work of literature written in a language other than English

and are impressed with what we read, we tend to lavish

praise on the writer but forget about the person who has

enabled us to read the book in the first place and who

sometimes spends as much time translating the book as the

writer did in composing it. Translation, particularly

literary translation, is not merely the transcription of a

work from one language into another; it requires a

recreation of the eloquence of the phrasing and the nuances

in tone of the original. Please continue to write about the

works of and about outstanding Turkish authors you find in

bookstores. They certainly need to be brought to the

attention of the readers of Today's Zaman. But in the future

please credit the translators of those works as well.

dimitrios macedon , 22 July 2012 , 17:35

Speaking today about Nazim is surprise, but it is good sign. |